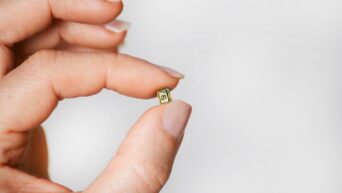

If you thought that 3D printing was already amazing, then wait ’til you hear this: researchers from the University of Michigan have announced the development of a resin-based 3D printing technology that is reportedly capable of printing up to 100 times faster than the current printing standards.

The study regarding this innovation was published in a recent edition of the journal, Science Advances. The technology involves the use of a special technique that uses two lights to control where resin remains fluid and where it hardens, allowing the process to go much faster since complex objects are built up in one shot, rather than in a layer-by-layer fashion.

Aside from this, the resins used by the researchers are unlike any other. While most resins are developed to have one reaction, that is, photoactivations, these new types of resin used by the researchers also included both a photoactivator and a photoinhibitor, thus enabling them to either harden or remain fluid depending on which particular light is used.

The way it worked in older models was by stopping the printing every time the hardened layer had to be removed from the tank. Fresh liquid resin would then be allowed to flow in and the process would be repeated to create the next layer. Although this method worked perfectly so far, it also created a very slow process of 3D printing, since having to do all these steps was quite time-consuming. Over time, the window transparency also degraded, messing up the print accuracy and eventually requiring replacement or refurbishment of the tank.

This new method can also be used to work with thicker resins, a feat that is pretty much impossible with the older 3D printing technology. This can offer strength benefits in terms of object quality since the parts of the objects will no longer be subjected to any weak points between the layers.

At the moment, there are three patent applications that have been filed for this innovative technology. One of the researchers, Timothy Scott, is also preparing to launch a startup company to commercialize the process, according to sources.