Scientists just figured out the hidden switch that could help immunotherapy save millions more lives

Scientists have finally cracked a mystery that has puzzled researchers for nearly 40 years. They now understand how T cells, one of the body’s key immune defenders, switch on to attack cancer. This discovery could make cancer immunotherapy more effective for many patients.

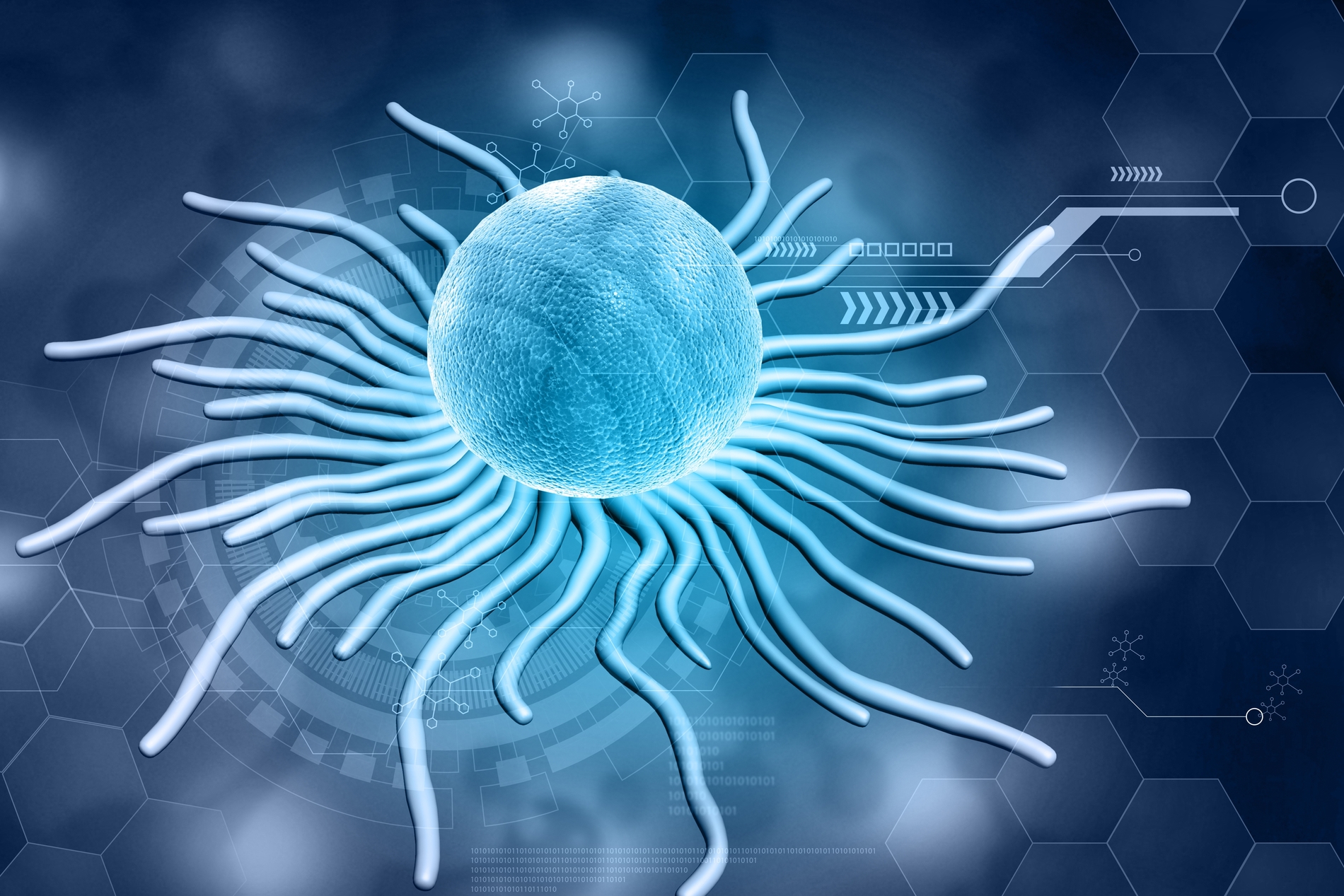

The research team at The Rockefeller University found that the T cell receptor behaves in a surprisingly simple way. When it is inactive, it stays tightly closed. It does nothing. But the moment it comes into contact with a cancer cell or another serious threat, it changes shape and opens up. This movement sends a signal inside the cell that tells the T cell to attack.

This was unexpected. For years, scientists believed the receptor was already open, even when the T cell was resting. That assumption turned out to be wrong.

This finding matters because T cell immunotherapy has already changed how some cancers are treated. These therapies train the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. In some cancers, the results have been life changing. In many others, the treatment barely works at all. Until now, no one fully understood why.

The breakthrough came from how the researchers ran their experiment. Ryan Notti, a cancer doctor and researcher, worked with microscopy expert Thomas Walz to study the receptor up close. They used a powerful imaging method called cryo electron microscopy. This allowed them to see the receptor in its natural state.

Earlier studies failed because the receptor was examined in detergent. That process removed it from its normal cell environment. It is similar to studying how a phone works after taking out its battery. The Rockefeller team avoided this mistake by placing the receptor into a tiny disc that mimicked a real cell membrane.

What they observed was clear. The receptor stays compact when resting. Once it detects a cancer-related signal, it opens and stretches outward. That movement is what carries the message into the cell and activates the immune response.

This new understanding could help scientists improve immunotherapy treatments. With better knowledge of how the switch works, researchers may design receptors that respond more easily to different cancers. It could also support the development of stronger vaccines.

For millions of cancer patients who do not benefit from current immunotherapies, this research brings real hope. It suggests that better and more reliable treatments may be on the way.